'Wirrinyiya ngaragngarag birra ngamoo ngamoo'

In this shelter, everybody has been making artefacts and paintings for a long time

An Exhibition marking the Twenty First Anniversary of Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency Aboriginal Corporation, Fitzroy Crossing

Introduction from the Chairman - Mervyn Street

In this shelter, everybody has been making artefacts and paintings for a long time.

These words come from the Chairman, Mervyn Street as he reflects on what it means for the art centre to be ‘grown up’, to be twenty-one. He is recognising the strength of the original artists and the work that they did in establishing the art centre.

"I have been Chairperson for a long time now. Some of the old people who elected me are gone, but others are still here, painting strong. Still today I am Chairman. I don’t really know why people want me here but I am happy to do this job. I can talk language and kriol in meetings so that old people can listen. I like doing this job, coming to Mangkaja, working to keep it running. I like to come here, to make my paintings, talk to the other artists and see what they are painting. It is a good place.

Mangkaja has been running for a long time. The first artists made it strong. This exhibition shows some of the older works and new ones. The Directors and workers at Mangkaja welcome you to this exhibition, to come and see some of the work that we have been doing here, for a long time now."

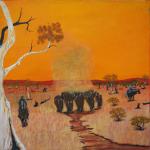

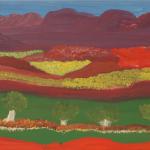

Mervyn is a Gooniyandi man who paints the river and ranges country of his mother and his jaja and japi (grandparents). He paints landscapes, Gooni (Dreamtime) stories, bush foods and hunting stories as well as images that tell of the work that he and his countrymen did on cattle stations across northern Australia. He has a strong didactic approach, taking on a leading role in teaching community kids in classrooms in Yiyili, Muludja and Fitzroy Crossing schools.

Making Mangkaja Strong

This exhibition marks a significant milestone in the growth of Mangkaja. The centre was established purely as a place to make and sell artefacts. As Ngarralja Tommy May said, you need to start from the beginning, “You have to think from the start, when Mangkaja first started it was an artefact place”. In the early 1980s the Aboriginal Arts Board of the Australia Council funded the construction of a modest concrete and tin structure to be used as a workshop for the production of artefacts. It was this building that led to the name Mangkaja, a Walmajarri word for wet weather shelters that the artists built in the desert to keep dry during the wet.

The actual process of building a strong mangkaja, a good structure, is given by Ngarralja as he says,

"In the desert you make mangkaja on the jilji (sandhills); you can’t build it on the parapara (low ground between the jilji). You have to build it on the jilji, to keep dry and stop it from washing away. You need strong wood to build it and a fire inside."

It is an appropriate analogy as it is the high points, not the troughs that have set the foundations from which the centre has grown. It is the drive to keep painting, the artists’ connection to country and culture and the artists’ pirlurr (spirit) that has continued to burn inside Mangkaja, that have made and kept the centre strong.

Gail Smiler who worked in Mangkaja throughout the 1990s and whose parents were painters reflected on the foundations thus,

"When people came from country, people were always thinking about country, they would sing for country. Singing for dancing is different to singing for country; I used to hear my father singing for country, crying. That’s why Mangkaja was strong, the singing and painting came together."

It is true that the artists would always fill the studio with a low hum, a gentle chorus of country that accompanied their work. While fewer artists sing while painting now, the strains of the songs still resonate through the recordings on video and audio tapes that play incessantly in the studio.

Reflection

In discussion with the artists to reflect on the achievements of the past 21 years, there was a range of responses with comments such as ‘only two women are famous in this place’, ‘not enough young people are working’, ‘I was excited to win’ [the art award] and ‘that washing machine is still going’. In these four responses, we get a snapshot of some of the concerns and expectations that artists have in the support that they get from art centres in remote communities. There is the problem of the art market’s habitual practice of singling out one or two favourites while ignoring others, the need to encourage and foster a new generation of artists, the desire to become ‘more famous’ through marketing and promotion of their work, and the value of income derived from painting sales.

Perhaps one of the most salient reflections was about the way older artists are encouraged to continue painting when they are frail. Ngarralja Tommy May recognises a point when artists should be left to rest as he says, ‘Really old people should not be pushed; when old people come and they can’t walk, they should retire’. His observations now loop us back to the lack of young people taking up painting. As with many remote art centres, there is a need to discover and encourage younger artists, although the new and emerging artists are at times the same age as the veterans. Jean Rangi is an example here. She is one of the newer artists working in Mangkaja despite being the contemporary of many of the established artists such as Amy Nuggett and Dorothy May.

This may not be as contradictory as it first appears. It is difficult for younger artists to find time and space to paint as they have responsibilities, particularly relating to family. Eva Nargoodah, a very fine painter would love to paint more readily but she has grandchildren who keep her away from the studio. There are other factors as well. The cultural maturation of individuals, their right to paint and the necessity to be sanctioned to paint by cultural leaders and elders, all impact on a person’s decision to paint.

As with other art centres, Mangkaja has provided a place for these processes to evolve, for younger people to work alongside family members. Eva came to painting through her grandmother, so her work hangs here with her grandmother’s paintings. Despite the fact that the works are markedly different, the confidence that Eva draws on in her work comes from watching as the older woman painted.

Murungkurr Terry Murray is another younger artist. Like Eva, Murungkurr is a fine painter who paints intermittently. He has a schedule that regularly takes him from Fitzroy Crossing to Perth and beyond and the time that he has available after work, he generally spends hunting with his boys. Here, Murungkurr relates the story of his first encounter in Mangkaja when he was in his early twenties. He recognises the seminal nature of this experience and the effect that it has had, and will continue to have, over his lifetime.

Planting the seed – Murungkurr Terry Murray

I have been thinking of the material from Karrayili (Adult Education Centre), how the old people were learning kriol and speaking English; they were really bouncing messages back and forward, [in different languages]; [I think of them] walking from the desert and going to school – to Karrayili. Some learnt to write their names, to count, to drive, and to paint.

The first time I came to Mangkaja, the team was there – Gail, Japarti, Heather and Neil. I was good at doing charcoal drawing on concrete floors just doodling or graffiti; I learnt this when I was growing up at Djugerari. At school I thought I was good, but then walking into Mangkaja for the first time was like a big wake-up. You walk into a room and you see all of this painting. It was fascinating just fascinating looking at the paintings. I didn’t know how to mix paint or anything. It was like filling up with fuel, looking at my countrymen painting. I looked around, it was all too much; Old Man [Peter Skipper], he was there cracking the whip and my jukurr (aunty) Wajina Honeychild with her brush in the corner, Mum Jukuna beside her and Butcher in the other corner, in the front.

Old Man said, ‘My boy, come here, I have to show you’ He was painting Japirnka – this was the first time I had seen this. I didn’t know much, I was like a young boy. It was just like he was planting the seed. I was really fascinated to see anyone can do painting. I was really fascinated, just looking at all of them with their own technique.

Old Man was showing me, naming all the jila and naming the family; then Wajina was saying ‘Come here’ and she told me about another area. I was so happy about that. People were pulling me from one end of Mangkaja to the other. I was so proud to see everyone was connected in country. I asked Japarti and Neil for paper. I didn’t want to ask them at first, I was frightened. ‘Give me scrap paper, to do some art’ I was so frightened, just looking at them. Paint I thought, is this not my style. I was good with charcoal and pencil.

I did my first painting, a landscape on paper and comparing it to all the artists like my Old Man and my jukurr Wajina, I said to myself ‘I am not an artist, painting is not for me.’ Little did I know then that I was next in line for this ngurrara, country jila business. I screwed that painting up and walked out. But it was like Skipper and Wajina and all that other artists were sewing the seed. In the future there won’t be much. The circle is getting smaller and smaller. We need to build Mangkaja up. The foundation is there so we need to rebuild it, how we see it in our own eyes and family members coming together to have a view of how Mangkaja will be.

It is good to see how people work day in day out, coming in and being part of Mangkaja, doing painting and projects, going back to country and getting strong through heart and soul. Always people talk about money – when will they get paid? Painting gives more than money. It can help with questions like ‘How do you satisfy yourself? What makes you happy? How you feed your family, how are you are respected in your community, - how you survive I guess’.

Looking back, looking forward

Twenty-one years ago, Tandanya hosted Karrayili, the first major exhibition of works by the artists from the fledgling Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency. Mangkaja was auspiced through the Economic Development arm of Karrayili Adult Education Centre and the title of the first exhibition gave recognition to the pivotal role that Karrayili played in the seeding of the art centre. Nineteen artists and five staff members travelled 4000 km in an old coaster bus to attend the opening. It was the first time that many of the artists had travelled beyond the Kimberley and the adventure became legendary.

In 2001, again the artists made the pilgrimage to Tandanya, travelling in a hired bus and the art centre Toyota. The occasion was their tenth anniversary exhibition. The number of artists had increased to twenty nine, commensurate with the developments that had taken place over the preceding ten years.

The early to mid 1990s were exciting time in the Kimberley with the High Court’s Mabo decision being a major event that sent ripples across the region. Mangkaja was caught up in the excitement as the opportunity came to travel back to traditional lands in the Great Sandy Desert and into the ranges and river country. The centre made many trips to artists’ countries, often in tandem with the Kimberley Land Council. The trips provided rich and rewarding experiences for the artists as they saw again, the county that they had known since birth. Many of the artists were young adults before they left their traditional lands. Seeing these places again infused the work with strengthened vision and the reaffirmation of their knowledge of their ngurrara and riwi (country).

Along with making the art centre’s first foray in to the desert in 1993, Mangkaja became independently incorporated under the Aboriginal Councils and Association Act. It followed the model of many of the art centres across the north and was run by an active, assertive and at times argumentative committee. The relationship with Karrayili remained strongest in the management style of the centre. Through their training at Karrayili, the artists had learnt the value of taking on the responsibility of making decisions as committee members and in instructing staff on policy and planning matters. The strength of the management committee has been a very positive aspect of Mangkaja since its inception.

While the emphasis has been on consensus decisions that would draw in all of the artists, there has also been recognition for individual artists in awards and prizes that they have collected. Daisy Andrews won the coveted National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award in 1994, Dorothy May was awarded the work on paper prize in 1995,Wakartu Cory Surprise received the same award two years later and Spider Snell was the winner of the painting category in 2004. More recently, In 2010 Wakartu Cory Surprise won first prize in the prestigious Western Australian Indigenous Art Award, Sonia Kurrara won the painting prize in the same event and Lisa Uhl was awarded the Kimberley Art Prize’s Emerging Artist Award in 2011.

Looking back, looking forward

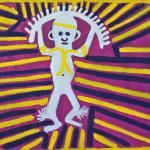

Several artists were also recognised by the Aboriginal Arts Board and the Dance Board of the Australia Council, awarding Janangoo Butcher Cherel and Nyirlpirr Spider Snell major Fellowships in painting and dance respectively. In the wake of such attention and success, Mangkaja’s exhibition program has grown steadily since 1991 into a strong and varied annual exhibitions program.

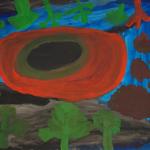

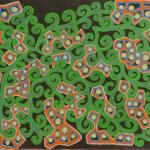

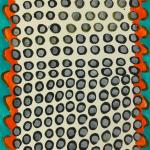

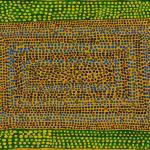

This current exhibition is not a comprehensive survey show. It gives a glimpse of the work produced by some of the centre’s key artists over the past twenty-one years. The initial section highlights the work of artists who were active in the 1990s. The first panel of four works recognises Daisy Andrews, April Jones, Nada Rawlins and Dolly Snell as the four women who exhibited in the first exhibition at Tandanya in 1991 and who are still painting today.

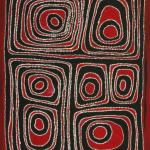

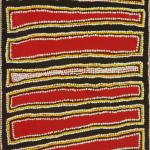

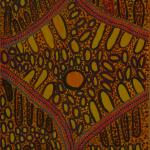

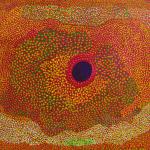

The next section focuses on early works on paper that characterised the Mangkaja works until the gradual transition onto canvas that began in the mid 1990s. These works are strong and emphatic affirmations of connection to country. While the first two sections of the show are dedicated to the memory of those artists who established the centre, the curatorial focus is not on the past. The clustering of works in family groups brings to the fore the threads of continuity that have been painted into the relationships between the older artists and their children and grandchildren.

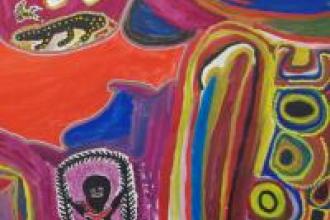

The younger artists, being supported by parents, grandparents, aunties and other countrymen, are clearly in good company. Lisa Uhl for example is one of the fledgling painters whose current works reveal the strength and possibility of greater works brewing within, while Graham Lands is gently calling on the works of his grandfather, the great Janangoo Butcher Cherel (dec) as he feels his way into his own unique, but distinctly connected aesthetic.

The countries for the Mangkaja artists fall broadly between the rich river and spring country in the northern reaches of the Fitzroy Valley and the desert to the south. This dichotomy has infused a strength and contrast between to two groups. This contrast is evident in the river works that are characterised by the rich fish and bush fruit quarry that is found in riverine areas and the pure desert landscapes produced by the Wangkajunga women.

How then should this work be read? The disparity between desert and river and the further visual impact of such a diverse range of styles can be disorientating. It may be necessary to move through the exhibition several times before your eye shifts some works back and pulls others towards you, just as Jukuna said, painting brings country up close; bring the paintings up close, they have much to tell about the country and the artists who know it so well.

You can purchase any of the artworks below in the Gallery.

To make an enquiry please contact:

Eleanor Scicchitano

Visual Arts Coordinator

Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute Inc.

Kaurna Country

253 Grenfell Street

Adelaide, SA 5000

Tel +61 8 8224 3218 | DD +61 8 8224 3216

Fax +61 8 8224 3250 | Email vaofficer@tandanya.com.au

www.tandanya.com.au